Hadamard gate

Contents

5.9. Hadamard gate#

This is another very important one-qubit gate. It changes basis set between \(\{|0\rangle,|1\rangle\}\) and \(\{|+\rangle,|-\rangle\}\). We shall call this gate simply HGate.

5.9.1. Definition#

Transformation

(5.11)#\[ H |0\rangle = |+\rangle, \qquad H |1\rangle = |-\rangle \]

This is the standard way to generate the \(x\)-basis ((4.2) from the computational basis.

Matrix expression

(5.12)#\[\begin{split} H \doteq \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 \end{bmatrix} \end{split}\]

U gate expression

(5.13)#\[ H = U\left(\frac{\pi}{2},0,\pi\right) \]

R Gate expression

\[ H = i \, R_x(\pi) \cdot R_y\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right) \]

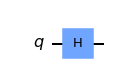

The Qiskit circuit code symbol is ‘h’ and it appears in quantum circuit as

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit

qc=QuantumCircuit(1)

qc.h(0)

qc.draw('mpl')

or

qc.draw()

┌───┐ q: ┤ H ├ └───┘

Exercise 5.9.1 Show that \(H^{-1}=H\). This means that the \(x\)-basis is transformed to the computational basis by \(H\) gates.

(5.14)#\[ H |+\rangle = |0\rangle, \quad H|-\rangle = |1\rangle \]

Qiskit Example 5.9.1 A common use of the Hadamard gate is to switch the basis set. In the quantum simulation of coin tossing (Qiskit Example 4.3.1) we have already used a Hadamard gate to generate \(+\rangle\). Here we flip \(|0\rangle\) to \(|1\rangle\) via the \(x\)-basis. First, we switch the basis from \(|0\rangle\) to \(|+\rangle\) by HGate. Flip \(|+\rangle\) to \(|-\rangle\) by ZGate. Then, switch back to the original basis by HGate. The final state is \(|1\rangle\).

This means \(X = H \cdot Z \cdot H\). In this example, the following process is visualized with Qiskit.

%%capture

from qiskit import *

from qiskit.visualization import visualize_transition

qc=QuantumCircuit(1)

qc.h(0)

qc.z(0)

qc.h(0)

movie=visualize_transition(qc,fpg=50, spg=1)

movie