Classical computation

Contents

3.1. Classical computation#

We carry out classical computation every day on many different devices, laptop computers, mobile phones, automobiles, smart TVs, refrigerators, … to name a few. These devices are made from semiconductors chips and optionally magnetic materials and their functionalities are governed by quantum mechanics. Nevertheless, we call them classical computer. Why? While the underlying physical processes are quantum mechanical, information stored and processed in these materials is classical. For example, macroscopic electric current and voltage, which are classical quantities, are used to store and process information. In other words, a large number of electrons are used to store even the smallest amount of information. In contrast, quantum computation relies on microscopic states , e. g., energy eigenstates in an atomic ion. In th following, we discuss what is the classical information and how it is processed in the classical devices.

3.1.1. What is classical information?#

We ask a question because we do not know something and try to find it. In other words, wey to get new information. But what is information and can we quantify the amount of information? To answer this question, information theory was developed in the first half of twenty century by Claude Shannon and others.

In essence, the amount of information we obtain is the amount of uncertainty decreased. If there is no uncertainty, there is nothing to ask. The undertainties arise in several different ways. The outcome of an event that is going to happen in future can be uncertain if we cannot predict it precisely. The uncertainty is due to the stochastic nature of the event. IIn another case, the event has already happened and some people know the outcome but we dont’ know it. For us, this is uncertainty but it is due to our ignorance. In either case, once we know the outcome, the uncertainty disappears and we obtain the information.

The uncertainty can be mathematically expressed as probability. Consider coin tossing. For tossing the coin, no one knows the outcome. However, we know that the outcome must be one of head and tail. We cannot predict the outcome because the motion of th coin is chaotic and thus the outcome is stochastic. Assuming the coin is ideal, the probability of finding head and tail ares \(p_\text{head} = \frac{1}{2}\) and \(p_\text{tail}=\frac{1}{2}\), which is the uncertainty associated with the coin tossing. The amount of the information (undertainty) is given by

which is known as Shannon entropy or information entropy. If base 2 is used, \(\log_2 2 = 1\) and we say one bit of information is gained. Here bit is the unit of the amount of information.

After the coin is tossed and landed on someone’s hand, the outcome is not known to us until the person shows it. The uncertainty is due to ignorance but the amount of information we will find remain the same.

Here is the general definition of the Shannon entropy For a set of all possible outcomes, \(\{\omega_1, \omega_2, \cdots, \omega_N\}\) where \(N\) is the total number of possible outcomes and the probability \(p_i\) of finding the outcome \(\omega_i\) for all \(i\) is defined, the amount of information is measured by

3.1.2. Classical bits#

Selecting one out of two possibilities is the simplest question. Coin tossing is one of them. In classical computer the smallest information unit has two possibilities \(\texttt{0}\) and \(\texttt{1}\), which are assigned to two well-defined physical states in the devices, e.g., \(\texttt{0}\) to \(0\) volt and \(\texttt{1}\) to \(1\) volt if the voltage is used.

Mathematicall, we use a variable \(b \in \{\texttt{0},\texttt{1}\}\) for a single bit. The computer consists of many bits, bit 0, bit 1, bit 2, ……. For convenience, we denote the bits as \(b_0, b_1, b_2, \cdots \) and altogether the information is stored in a string of n bits, \('\, b_{n-1}\, b_{n-2}\, \cdots\, b_1\, b_0\, '\), for example ‘0010101’ (in this book, the bit string is in single quotes.) Notice the order of bits in the string. It is the standard to write string from the right to the left.

3.1.3. Copying a state of bit#

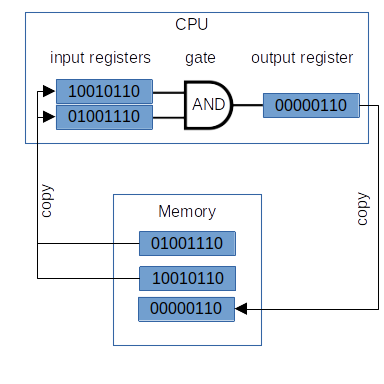

In classical computers, the information is stored as bit strings in random access memory (RAM). To process information, the bit strings are copied to the central proccessing unit (CPU). After the information is processed, the outcome is copied to some location in RAM. Copying the bits is a fundamental aspect of classical information processsing. As you see below, the input information is usually lost in during processing in CPU. In contrast, quantum computation does not have such luxury since cloning of quantum state is not possible (no cloning theorem).

Fig. 3.1 A schematic diagram of information flows in a typical classical computer. The state of classical bit can be copied to another classical bit with no restriction.#

3.1.4. Gates#

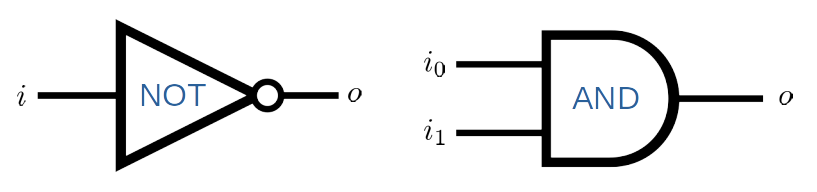

The computer can change the state of any bit as directed by a program. A simple operation is to flip a bit, that is \(0\rightarrow 1\) and \(1 \rightarrow 0\). We express it using a concept of gate. A bit enters a gate and comes out with a different value. In the classical computer, there are only two possibility, no flip or flip. “No flip” means nothing happens to the bit and thus we are not interesting it. The gate that flips a bit is called NOT gate. (See Fig. 3.2.) This is the only gate acts on a single bit outputs a single bit. The relation between the input and the output bit is given in the truth table 3.1.

|

\(i\) |

|

\(o\) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0 |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

0 |

|

Classical computation uses various kind of gates which takes two input bits (\(i_0\) and \(i_1\)) and outputs one bit. For example, AND gate outputs \(i_0 \times i_1\). (See Fig. 3.2.)

The corresponding truth table is given in Table 3.2. Notice that this process is irreversible, meaning that we cannot recover the input information \(i_0\) and \(i_1\) from the output \(o\). Hence, we says that a bit of information is lost. Two-bit classical gates are in general irreversible and 1 bit of information is lost. However, this is not a major issue since classical bits can be cloned and saved in a separate bit string.

In principle, classical computation needs only \(\texttt{NOT}\) and \(\texttt{AND}\) gates. It is using other gates makes classical computing much more efficient.

|

\(i_0\) |

|

\(i_1\) |

|

\(o\) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

|

0 |

|

1 |

|

0 |

|

|

1 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

Fig. 3.2 An example of classical gates. The \(\texttt{NOT}\) gate takes one bit and output one bit.#

3.1.5. Landauer principle#

The irreversibility of classical gates has important physical consequence. Landauer’s principle states that the loss of one bit of information necessarily dissipates \(k_B T \log 2\) of heat. For example, every time an \(\texttt{AND}\) gate is used, at least \(k_B T \log 2\) of heat must be generated. This heat is actually minute and much smaller than Joule heat that makes CPU really hot. Therefore, it odes not causes a significant problem. However, it imposes a theoretical limit of classical computation. In contrast, quantum computing is reversible and thus no dissipation is mandatory.

Exercise Is \(\texttt{NOT}\) gate reversible?

3.1.6. Encoding#

The computer can understand only bit strings and manipulates them by applying gates. However, problems we want to solve are usually not expressed in bit strings. Somehow, we need to map the problems to bit strings the computer can understand. In other words, we need to encode the information in our expression to the bit strings. As a simple example, we consider a boolean operation between two logical variables \(x\) and \(y\). Their value is either \(\texttt{True}\) or \(\texttt{False}\). Since the valiables takes only one of two possibilities, the mapping between the boolean variables and bits are naturally

Now, variable \(x\) is expressed by a bit \(b_0\) and \(y\) by \(b_1\).

In many problems, encoding is not obvious at all. Integer numbers can be mapped to bit strings using their binary expressions. For example, \(5 \Rightarrow \texttt{101}\), which requires three bits. Exact encoding of continuous numbers is not possible since bits are digital. Approximated representation such as floating point arithmetic numbers are used.

3.1.7. Instructions#

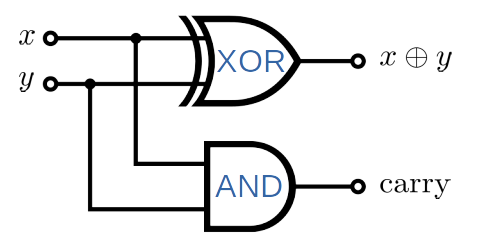

Computation means that by manipu, quantum or classicallating the state of bits toward the solution. The device can flip the specified bits . It can be thought of bits entering a gate and coming out with different values. We need to instruct the device how to change the state of the bits. In other words we to find find what gates should be applied to the bits. Let us consider a simple operation \(x+y \mod 2\) where \(x, y \in \{0, 1\}\). WE shall write this operation simply as \(x \oplus y\) . We map \(x\) and \(y\) to bits \(b_0\) and \(b_1\). Applying an XOR gate on \(q_0\) and \(b_1\) produces desired outputs. The following diagram classically computes \(x \oplus y\) and the output is stored in \(x\). The value of \(y\) remains the same.

Fig. 3.3 An example of classical circuit. This circuit computer \(x \oplus y\) using \(\texttt{XOR}\) and \(\texttt{AND}\). In addition to the answer, carry over bit#

In real world applications, we don’t apply the gates by ourselves. Instead, we use a programming language such as python. The language translates the mathematical expression such as \(x + y\) into gate instructions. So, we really don’t need to know about the classical gate. Quantum computation has not reached that level yet. Users must picks appropriate gates by themselves.

3.1.8. Readout and decoding#

Once the computation is completed at the device level, we need to read out the values of the bits and decode the outcome to an integer. The readout of the classical bits can be done without damaging their state. The value of the classical bits remains the same before and after the readout. (That is not the case in quantum computers.)

Last modified on 08/30/2022.